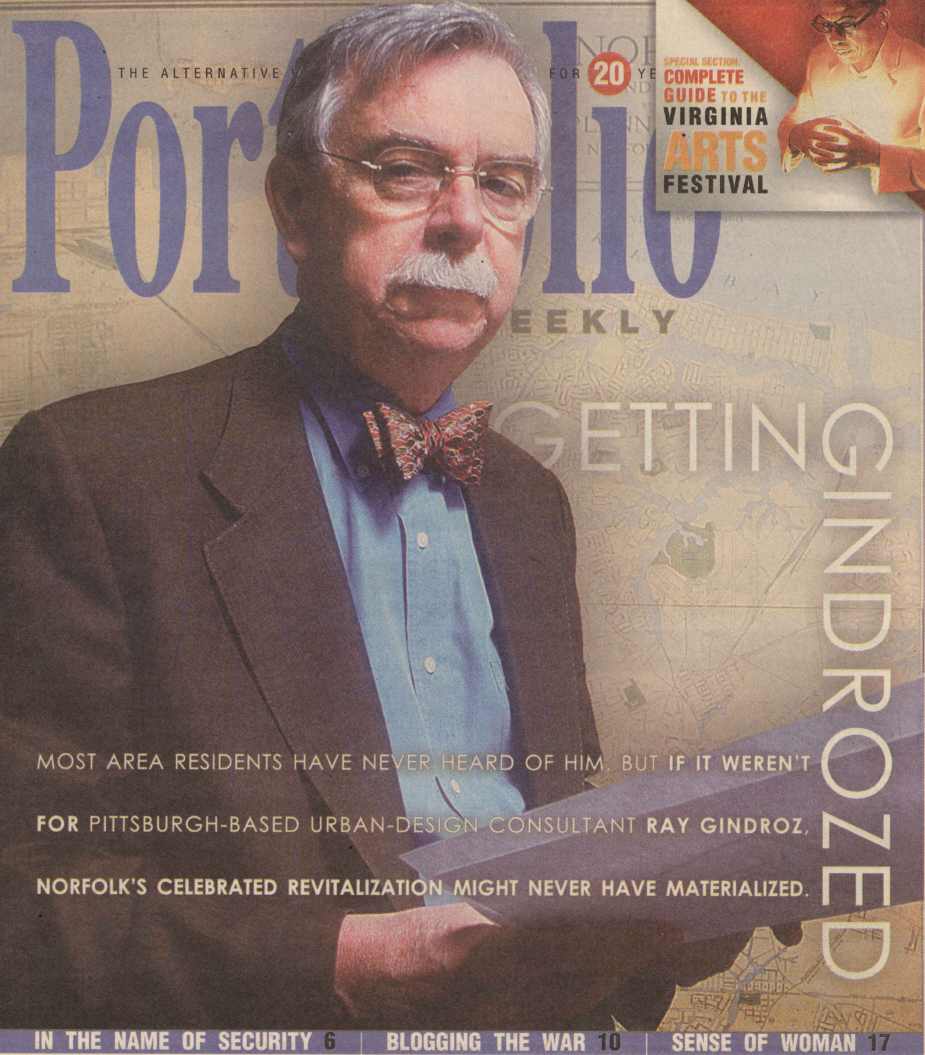

Local developers call it "getting Gindrozed."

They know if they have a major project in Norfolk, their plans will have to pass under the watchful eyes of Ray Gindroz, the consultant from Urban Design Associates, a Pittsburgh firm that has guided the city for more than a decade.

There may be no better symbol of Gindroz's pervasive influence in Hampton Roads than the transformation of his name into a verb.

"To have a project Gindrozed is usually good for it, though it at times frustrates developers who by nature want to do things as quickly as possible," said Robert M. Stanton, the longtime local developer. "But it's wonderful for the city."

Walk through the prominent public spaces in Norfolk, Portsmouth and Suffolk and you'll likely experience Gindroz's guiding hand. There’s a harmony, what he calls a “congeniality” to the best places.

"He's had a tremendous impact on at least three of the cities here," said David Rice, the retired executive director of the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority who first brought Gindroz to the area.

In Norfolk, officials rely heavily on Gindroz, who knows the city as well as any native and has worked on more than dozen major projects. In Suffolk, he helped create the city's design guidelines and has shepherded major initiatives including the downtown plan, the hotel and conference center at Constant's Wharf, the village plans and the East Washington Street plan. His guiding hand also appears in Portsmouth, where he's worked on the waterfront and nearby residential development, though he has no current projects there. And Hampton, impressed by his successes on the other side of the water, recently hired his firm to help revise its community plan in key areas like the downtown, Buckroe and North King Street.

It is Norfolk, though, where the range of his influence and the success of his working methods can best be seen. He makes monthly visits, usually for a day or two, to consult with city officials as well as business and civic organizations.

Since Norfolk hired his firm 16 years ago, Gindroz has shaped both the broad outlines and the pointilist details of the city's revitalization. During a one-day visit last month, he offered advice on controversial, big-picture, master planning issues like the $260 million University Village and the residential development near the Harrison Opera House. But he also made suggestions about details like the color of brick for condominiums in Freemason Harbor and whether an unsightly elevator ought to be removed from Selden Arcade, where he enthusiastically endorsed plans for an artists' colony.

"When we think we have a good idea," said Mayor Paul Fraim, "people generally say, 'I wonder what Ray will think about this. ' "

In Gindroz, the city has a consultant with an unusually wide range of skills. The former Yale University architecture school instructor is a facilitator able to speak comfortably with civic groups, developers, architects and politicians. He is an urban planner with a love of the great European Renaissance cities he has explored on his travels. He is a designer with an ability to synthesize the character of a city and create principles that build upon the strengths of the vernacular architecture. And he brings a range of experience working in cities like Cincinnati, Charlotte, Cleveland, Louisville, Baltimore, Yorkshire, England and Celebration, the high-profile Disney development in Florida.

"We have developed a great deal of confidence in Ray's ability and in his guidance," Fraim added. "He is a great strategic thinker as well as being very mindful of the details."

In the city, Gindroz has an enthusiastic partner. "Norfolk has understood for some time that good design is not simply to make things nice," Gindroz said. "It is actually a tool for economic growth and development. That's the key."

During a luncheon speech in February before city officials and neighborhood leaders in Hampton, he elaborated on his core principles while outlining how they had worked in Norfolk. "The key is to find a way to mobilize the energy of the community," he said. "The planning process is a bandwagon. You have to have as many people possible building that bandwagon. Once they've built it, they're already on board, moving together under a banner of a vision of the future."

Gindroz advocates creating a vision that builds on the character of a place, then marketing that vision. "Planning," he added, "is an entrepreneurial act, an optimistic act, saying the future is going to be better than the past. Planning at its best creates what I like to call economic flypaper. It puts out a vision that attracts investment, that attracts people to it."

Gindroz and his firm were instrumental in devising plans for Norfolk's downtown as well as the 2000 and 2010 master plans for the city. The list of past and present projects bearing the firm's fingerprints is extensive. They begin with MiddleTowne Arch, a residential development near Norfolk State University designed in the mid-1980s. They include the upscale MacArthur Center mall, where Gindroz lobbied forcefully and persistently for the developer to create a street-friendly facade on Monticello Avenue to better integrate the mall's enormous footprint into the downtown. They also include Diggs Town, the first public housing project in the nation with porches and other amenities, features that have been since become part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development's guidelines for public housing.

Gindroz’s current projects in Norfolk include:

n the ongoing downtown redevelopment.

n residential planning for the area near the Harrison Opera House.

n the Lafayette Boulevard commercial corridor.

n proposed academic and commercial buildings by Norfolk State University south of Brambleton Avenue.

n The East Beach development and the realignment of Shore Drive.

n the cruise terminal design downtown.

n Broad Creek Hope VI housing replacing Bolling and Roberts Parks.

n neighborhood efforts in Fairmount Park and the Church Street area.

n University Village

The city’s base contract with UDA calls for Gindroz to be paid $210,000 this year, including expenses for travel and lodging. When he takes on additional projects like University Village, he is paid more. In some recent years, he has been paid more than $300,000 by the city.

His monthly treks to Norfolk are crammed with meetings and evaluations. Last month, he began his one-day visit by meeting with Rod Woolard, the city's development director, and the developer for St. Paul's Place, an apartment complex in East Freemason Harbor.

Then he settled into a fifth floor conference room in City Hall with Jim Gildea, the assistant director of planning, and Mary Miller, the manager of housing services. When projects run into snags, Gindroz gets a call from the city. Sometimes the call comes from City Manager Regina V. Williams. Sometimes it's from Assistant City Manager Shurl Montgomery. And sometimes it's from Fraim, who has cultivated a passion for good design and a willingness to push for it.

Gindroz is careful to point out that these sessions are not about whether a project matches his design tastes. They are reviews to ensure projects weave seamlessly into the city's urban fabric and support the ideas and design principles developed over more than a decade. A central tenet of those principles is synergy, using every project to create another project.

The first project on the agenda last month was his firm's reconsideration of the University Village redevelopment already under construction by Old Dominion University. Gindroz had helped conceive the idea for a village with a Main Street integrating the campus neatly into the fabric of the city first unveiled in 1997. Somewhere over the years, the design took a decided left turn.

By the time Fraim saw nearly-finished plans for a retail block that included an expanse of parking and big box grocery store last fall, he reached for the phone to call Gindroz. The city had envisioned a unique academic village; the plans resembled a suburban shopping strip. So the city offered to pay for Urban Design Associates work on the project as a gift to ODU.

Parachuting in after the university thought it had approved plans for the development of an expensive piece of land is a tricky assignment. But Gindroz seemed unfazed.

As he discussed the ideas illustrated by a drawing generated by his staff, he began "Gindrozing" himself. His staff had drawn a plan moving a proposed grocery store off Hampton Boulevard to Monarch Way to connect with new housing and office buildings proposed for that pedestrian-friendly street. They'd also prepared sketches of proposed building facades. On Hampton Boulevard, where there is more space, the facades would be grander, more massive, closer to the street, while on Monarch Way they would be smaller, the plane stepping back on the top floors so they were more in scale with nearby residential buildings.

As he continued discussing the plan, though, questions arose. Why put the office buildings on Monarch Way, far across Hampton from where the university has offices? Why not make Monarch Way an even more obviously pedestrian environment?

Maybe, Gindroz suggested, Hampton Boulevard and Monarch Way should be different in more than just building sizes. Maybe they should be different in use. Maybe Hampton Boulevard should be a grand boulevard of offices and the Ted Constant Convocation Center while Monarch Way is predominantly residential with ground floor retail where feasible.

"Our mission was to do design guidelines and modify the retail along here," he said, pointing to the area of the proposed grocery store. "But what we’re finding is the (overall) plan is flawed." Gindroz promised to have a new plan by his visit this month.

Then it was on to something much smaller in scale, the retail facade for the first floor of a parking garage at 100 Granby Street. The cavernous space, owned by the city, is dark and uninviting. An architect had proposed a few cosmetic changes that Gindroz thought didn't quite work. "I would go in a different direction," he gently told the city staffer presenting the drawings. He suggested using arcades like those found in Turin, Italy, as a starting point, opening up the space and lighting it better. "This is tough. Tough," he added.

Next were plans for apartments on Boush Street with a parking garage rising behind them. Gindroz worried about the garage being too tall, out of scale with the apartments. He was concerned about the lack of retail on the bottom floor, a design idea he'd successfully campaigned for across the street in the Heritage at Freemason Harbor, the mixture of residential and retail opening onto the west side of Boush Street. And he was concerned about the developer's alignment of the apartments, long deep tunnels stretching back from the street. "When we get the drawings, let's review this," he said, "We're going to need to be tenacious on this one."

As Gindroz met with planners, a team from Urban Design Associates was down the hall in a conference room doing a charrette creating ideas to revitalize Lafayette Boulevard for an afternoon presentation.

He lunched with Fraim for an hour and a half, discussing a handful of projects including University Village, Freemason Harbor, St. Paul's Place, Granby Street and the proposed Norfolk State University development. The two also walked through Selden Arcade, which the city is transforming into a new home for artists.

"He let his mind wander and it was remarkable to hear all the ideas," Fraim said. Foremost among them was removing the elevator that juts into the arcade. Then the two took a ride through Freemason Harbor, where Gindroz checked on the residential projects and typically made suggestions about a detail -- the color of brick.

Over the years, Gindroz said UDA has learned that the right architectural details can make the difference in creating a successful place. "We're finding increasingly it's not all details, but some details that are essential to creating this quality of urbanity I liken to a congenial urban space," Gindroz explained later. The character of windows are important. The way paving patterns work. The atmosphere created by lighting matters.

"There needs to be a certain level of order and scale that's comfortable," he added. "You put a mercury vapor light in a small-scale pedestrian space and it will look like a prison camp instead of a pleasant residential lane."

When Gindroz returned to City Hall, City Manager Regina Williams called to say time was tight, but she needed a few minutes with him. A few minutes became two hours as they discussed half a dozen projects.

Back with Gildea in the conference room, Gindroz met with Jim Gehman of the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority for a conference call with architects from Sasaki Associates. The Boston firm had prepared a preliminary sketch siting a series of academic and commercial buildings proposed by Norfolk State University south of Brambleton Avenue. They moved a proposed light rail line slightly to align the buildings along Brambleton and Park Avenue. "We're behind what you're doing 100 percent," Gindroz told them. "It's a great scheme."

With that, Gindroz hustled to Hampton, where he was meeting with city officials who recently hired him. He didn't have time to discuss another favorite project of his, a "pattern book" of suggested home types and design details for Norfolk neighborhoods.

"I love cities. I love urbanism," Gindroz said in an interview a week after his March visit. "The fundamental qualities of urbanism are what I think makes civilization work. I enjoy being in urban spaces."

Gindroz has lived in Pittsburgh's Squirrel Hill neighborhood since he graduated from Carnegie Mellon University. Within roughly a quarter mile of his condominium, he says there are two bookstores, three Starbucks, five banks, a supermarket, a major bus line and a diverse range of housing. "It's the kind of place we'd design," he said.

In his talks, Gindroz shows a slide of Paris, a view from the inside of a drawing room looking out into the city. He sees the streets of a city as urban rooms, the inside intersecting with the outside. "My primary interest is in the character and quality of public space," he explained.

Since he won a Fulbright scholarship to study for two years in Italy after graduation in the late 1960s, he has traveled frequently, drawing wherever he goes. An exhibit of his sketches will open July 4 in a bookstore in Milan, Italy.

He is on the board of the Congress for New Urbanism, the high-profile proponent of traditional neighborhood design. But Gindroz and UDA were working on urban spaces long before anyone coined the term "new urbanism." They called it neotraditional design.

"A lot of us had been working in cities for a long time trying to transform the word 'urban' from a four-letter word into a word of respectability," Gindroz said. "For a very long time, it was the first name for all the problems our society faced."

Ironically, the new urbanists like Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk of DPZ, the Miami firm, made their names in the early 1990s imposing urban forms on new towns designed in suburban settings, places like Seaside, Florida and Kentlands, Maryland. Gindroz and UDA created the pattern book, the collection of permitted design templates for Celebration, another new town created by Disney and designed by the preeminent New York architecture firms, Robert A.M. Stern Architects and Cooper Robertston & Partners.

Robert A.M. Stern, the dean of the Yale University School of Architecture and one of the most prominent postmodern architects in the country, described Gindroz as "an important person in the field."

"Thirty years ago there was no sense of the value of the traditional American town. There were nice neighborhoods, often being abandoned by people moving to more rural settings or escaping what they perceived of as urban problems," Stern said. "But there was no real discussion of why the neighborhoods were nice for 50 or 60 years and whether new neighborhoods like that could be created. Ray and many others -- and Ray was there at the beginning -- argued for analyzing these neighborhoods, seeing what made them desirable visually and sociologically and then seeing if we can have more of them."

Stern noted that in places like Norfolk, Baltimore, Celebration and elsewhere Gindroz doubled as both a designer laying out the streets and public spaces and as a "code maker" creating a sort of "grammar book" - the pattern books and design guidelines - to guide architects and builders. The Gindroz pattern books, he said, explain a vocabulary of details that make up something called a style. And they address the difficult problem of building simply within market realities.

"It is a fresh take on the methodology of translating an urban ideal into an urban reality," Stern added.

Gindroz and Urban Design Associates literally have written the book on the subject, publishing "The Urban Design Handbook" (W.W. Norton) earlier this year. The book lists three simple core principles:

-- Find the best things about a place, then protect them and build on them.

-- Find the worst problems and design ways of making them better

-- Make sure to use the new things to connect the best things in ways that fulfill the dreams of the people we serve.

The firm relies heavily on visuals, having abandoned lengthy reports years ago. Among them are colorful "X-rays," boldly and simply showing street grids, settlement patterns, railroads and industrial uses, open space, patterns, topography and anything else necessary to understanding the area regionally and locally.

Typical of the visual approach are the slides Gindroz shows of Norfolk's downtown development in 1980, 1990 and 2000. One slide colors intended development in red, then Gindroz flips to the next one showing completed development -- far more than the plan anticipated. The red areas also show an increasing number of connections linking Granby Street downtown with residential development in Freemason Harbor and Ghent Square.

His plans are flexible, though. During his Hampton speech, Gindroz showed a slide of a proposed new arena just south of Scope. Clicking his mouse, the arena morphed into a residential site with the same corner brick facade. "When you do a plan, there are always contingencies, " he said. "You don't know exactly what the market's going to be in two years, three years, even a few months. But you have to sense the physical form and framework that creates a vision people will rally around."

Gindroz is an eloquent, quietly passionate speaker. He dresses more like a professor than a businessman, on a typical day favoring a brown suit with a muted blue stripe, blue shirt, matching brown, maroon and pink bow tie and blue beret.

H. Blount Hunter, a retail researcher in Norfolk formerly with The Rouse Company, has worked on teams with Gindroz in other cities. He also oversees his work as a board member of the ODU real estate foundation developing University Village. "Ray's great contribution is that he inspires people," Hunter said. "He has the ability to extract aspects of a community that should be greater sources of pride than they might actually be today."

Fraim, Stanton and R. Steve Herbert, Suffok's city manager, said they admire Gindroz's ability to create a design and go out and sell it to a wide variety of constituents. "There's a remarkable trait he has," said Herbert, who has worked with Gindroz in Portsmouth and Suffolk. "He has an ability to talk about every street as if he's lived in this neighborhood. You can see people shifting from listening to a consultant to listening to a guy who really knows what is going on in their neighborhood. In the years I've been working with him, I've never seen him miss, never heard him call a street by its wrong name. He has a remarkable ability to understand the neighborhood and understand the issues people have."

Herbert said Gindroz masterfully navigated the difficult issues of East Washington Street, a predominantly African American downtown area that historically had a distrustful relationship with the city. "He was able to weave it all together down there into something that for the first time made sense," Herbert added. Residents united behind his plans to bring residential and retail development to the area and the City Council responded by pledging every penny of Community Development Block Grants for the next five years to the project.

Gindroz is pragmatic enough to know that he won't win every design argument. Hunter calls him "a practical optimist, a practical perfectionist."

He's also a cheerleader reminding cities that their time has come and they can afford to demand good design. "Ray is always saying don't back down," Hunter said. "Don't go with your hat in hand. You have more going for you as a city. Insist upon the best. Ray believes Norfolk and other urban areas are in the path of some fundamental market forces that are favorable to them after years of those forces favoring suburbs."

He says Gindroz has mastered the ability to be both comfortable insider and critical outsider.

"I think Ray can come in and walk a very fine line between being the proudest local citizen and the most detached outside observer," Hunter added. "And there's great value in that."

Gindroz first came to Norfolk in 1986. Early on, he found himself in a small plane flying over the area. "My impressions were and continue to be that it's always a surprise when you get off of the less attractive main roads into a very rich collection of neighborhoods. I draw a parallel to Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh is a city with a lot of topography, which creates boundaries and definitions for neighborhoods, which I believe contributes toward the long-term stability of that city. There are identifiable places of scale which generate a strong emotional attachment on the part of the residents," he said.

"Norfolk has no topography, but it has these inlets, which really result in the same thing. You have boundaries for neighborhoods and discontinuities in the urban fabric...I think Norfolk's great asset, one of its many great assets, is the stock of its neighborhoods."

His first project was for the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority, struggling with developing land cleared near Norfolk State University that had been Liberty Park and would become Middletowne Arch. The city wanted to create an industrial site, but neighbors resisted. NRHA suggested a residential development, but the market was iffy.

"We kept doing site plans trying to figure out how to do it," remembered Dave Rice, the longtime executive director of the NRHA. "We couldn't come up with anything that made much sense. He came up with a terrific plan that extended the athletic fields along the interstate to buffer the neighborhood and picked up on the idea of arches like Mowbray Arch and Colonial Place Arch."

The plan was pure Gindroz: look to a city for its strengths and build on them. Developers loved it. That led to work in Ocean View and eventually Diggs Town, a blighted public housing project.

Gindroz and Rice had strong feelings that good design could create the conditions for positive change there. "The bad places are where bad things happen and they're always where there are major design problems, fundamental design problems," he said.

So they came up with a bold plan for the $17 million Diggs Town redevelopment, abandoning the typical public housing "park" based upon Socialist models and instead creating a neighborhood with input from residents. New streets were cut through blocks. Residences were given backyards and play areas. Private porches, previously considered "frills" not permitted under federal funding, were added to increase safety – an answer to Jane Jacobs' call thirty years earlier for "eyes on the street."

"The turnaround of Diggs Town was extremely fast," Gindroz said. "It's become a national model. We used it to change HUD policy."

After HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros visited Diggs Town in the early 1990s, he invited Gindroz to Washington to help rewrite the guidelines for what is now called Hope VI housing.

About the time Gindroz began working on Diggs Town, he also turned his attention to downtown Norfolk. His guiding principle turned downtown development on its head: residents first, then retail. The economic development a city can attract to a downtown, Gindroz said, is inextricably linked to the residential. It's not so much just the numbers of consumers downtown, but what they say about the area.

"The presence of people living downtown is the absolute key to revitalizing downtown as the kind of commercial and business and cultural centers that they have become in the 20th century," he said. "It's a way of diffusing the old myths of it being unsafe downtown because with people living there you know it is a place that's cared for and managed by people who are there 24 hours a day, seven days a week."

Blount Hunter calls the plan for revitalizing downtown the "Norfolk model" and credits Gindroz along with former Council member Mason Andrews, Rice and others for being the major thinkers behind it. The model, Hunter said, called for solidifying office space, using entertainment to remove the fear factor, clustering civic, theater and museums for a regional draw, growing the restaurant base and adding residential.

"Ray and others understood the strategy of making the downtown important to the region, unique within the region and clustering multiple uses and reasons for being downtown," Hunter added.

The timing also was good. With the publicity surrounding new urbanism, downtown no longer was synonymous with ghost town. And then came MacArthur Center mall, the crowning achievement and a rarity -- a successful urban mall. Stanton credits Gindroz and his persistent, forceful call for connections to downtown, something originally resisted by the developer.

Stanton called the downtown success story “unique.” Unlike other cities like Denver, Norfolk's downtown wasn't revitalized during boom times. The boom times never came here.

Now, Gindroz considers Norfolk’s downtown a major marketing opportunity for the region.

"One thing that's interesting is the scale of downtowns compared with the population in the region," he explained. "Because water separates the towns, you have five downtowns. Norfolk has succeeded in becoming the center of the region, but its downtown feels like the downtown of a much smaller place and therefore has great appeal to the tourist and visitor market."

What lies ahead? Gindroz continues to push for residential linkages between Ghent and Granby to create a seamless urban feel. "It's important to get a human presence around the opera house," he said. "There's room for some residential, but what we've been trying to do is too intense."

What could the city do better? "Good question. The trouble is they generally take my advice, which constantly amazes me," he said, laughing. The city's commercial corridors are a problem, he said. And there needs to be continuing work on street improvements.

"But generally the city does a good job," he added. "I don't say that easily because we work with a lot of cities that don't do a good job."

Stanton said part of that good job has been relying on Gindroz and his team.

“Our children will appreciate what Ray Gindroz did for Norfolk during the time on his watch here," he added. "Good design lives for generations... So does bad design."

---end----

Jim Morrison can be reached at jimmor@aol.com. His stories have appeared in The New York Times, Smithsonian, This Old House, The Wall Street Journal and numerous other magazines.

BOX:

Gindroz’s current projects in Norfolk include the ongoing downtown redevelopment, the cruise terminal design, residential planning for the area near the Harrison Opera House, the Lafayette Boulevard commercial corridor, development of academic and office buildings by Norfolk State University south of Brambleton Avenue, the East Beach development and realignment of Shore Drive in Ocean View, the Broad Creek Hope VI housing replacing Bolling and Roberts Parks and neighborhood projects in Fairmount and the Church Street area.

|

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

Travel

Travel

Culture

Culture

Sports

Sports

Environment

Environment

Business

Business

Bio

Bio

Photos

Photos

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog