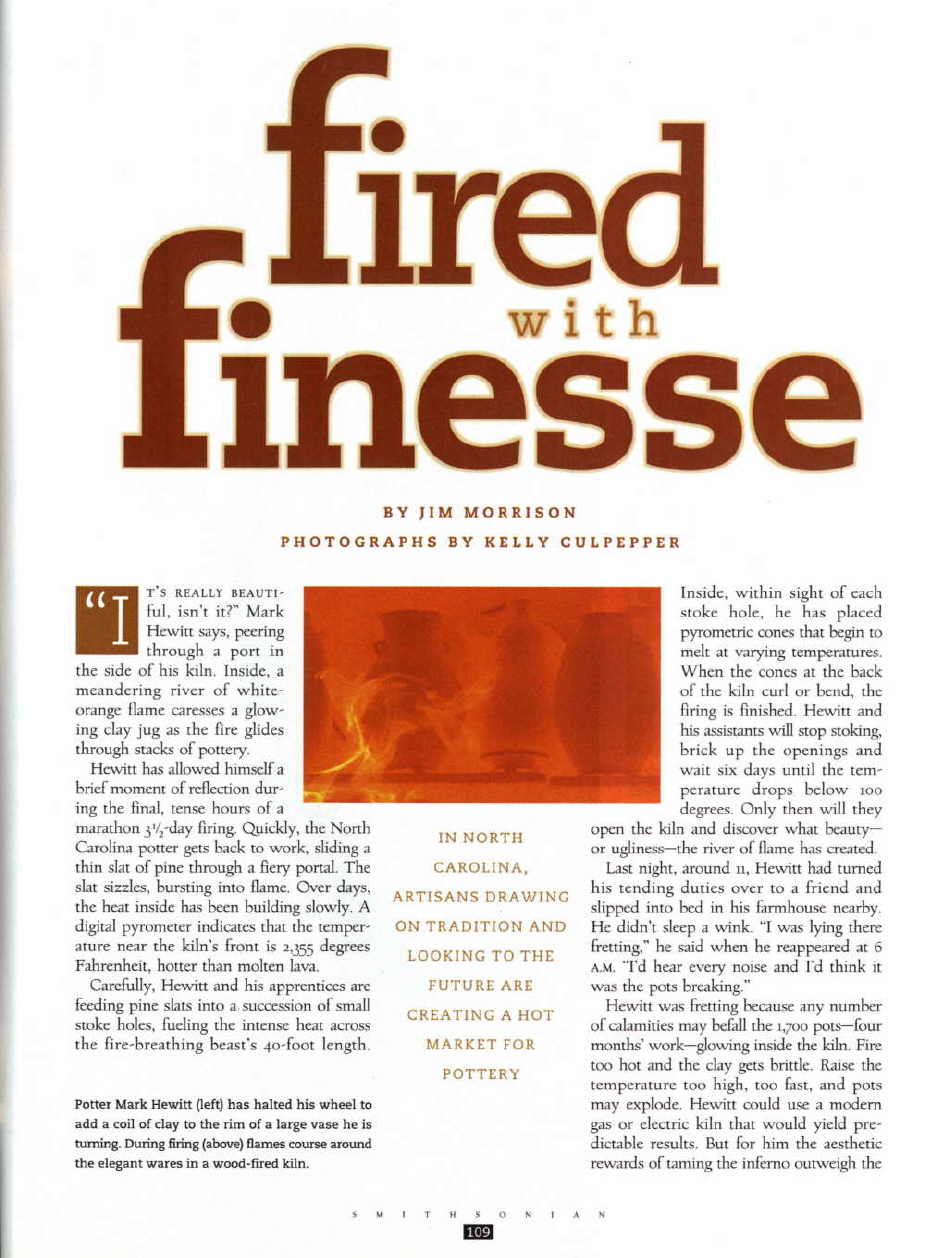

“It’s really beautiful, isn’t it?” Mark Hewitt says, peering through a port in the side of his kiln. Inside a meandering river of white-orange flame caresses a glowing clay jug as the fire glides through stacks of pottery.

Hewitt has allowed himself a brief moment of reflection during the final, tense hours of a marathon three-and-a-half-day firing. Quickly, the North Carolina potter gets back to work, sliding a thin slat of pine through a fiery portal. The slat sizzles, bursting into flame. Over days, the heat inside has been building slowly. A digital pyrometer indicates that temperature near the kiln’s front is 2,355 degrees Fahrenheit, hotter than molten lava.

Carefully, Hewitt and his apprentices are feeding pine slats into a succession of small stoke holes, fueling the intense heat across the fire-breathing beast’s 40-foot length. Inside, within sight of each stoke hole, he has placed pyrometric cones that begin to melt at varying temperatures. When the cones at the back of the kiln curl or bend, the firing is finished. Hewitt and his assistants will stop stoking, brick up the openings and wait six days until the temperature drops below 100 degrees. Only then will they open the kiln and discover what beauty- or ugliness- the river of flame has created.

Last night, around 11, Hewitt had turned his tending duties over to a friend and slipped into bed in his farmhouse nearby. He didn’t sleep a wink. “I was lying there fretting,” he said when he reappeared at 6 a.m. “I’d hear every noise and think it was the pots breaking.”

Hewitt was fretting because any number of calamities may befall the 1,700 pots -- four months work -- glowing inside the kiln. Fire too hot and the clay gets brittle. Raise the temperature to high, too fast, and pots may explode. Hewitt could use a modern gas or electric kiln that would yield predictable results. But for him the aesthetic rewards of taming the inferno outweigh the financial gamble. “This is the hard way of doing it. It’s very labor-intensive. It requires skills that you learn only by doing,” he said the day before, during a break. “I feel like the last of the dodoes.”

The pottery tradition in North Carolina, as rich as the local clay deposits, attracted the British-born Hewitt to the eastern Piedmont in 1983. When he arrived, there were only about nine or ten potteries in the area. Most of the owners were from families like the Owens, the Coles and the Teagues, who have created the area’s utilitarian stoneware going back many generations.

Now, more than 90 potters ply their craft in and around Seagrove (pop. 244), about 35 miles southwest from Hewitt’s farm in Pittsboro. Hundreds more are spread throughout the state. Those numbers reflect the resurgent popularity of home grown pottery in North Carolina. Customers travel from afar to attend kiln openings, often arriving at dawn to get a coveted spot at the front of the line. Many shops, however, stay open year round. Museums throughout the state have staged exhibitions featuring local potters. The $2.1 million North Carolina Pottery Center in Seagrove opened two years ago. Built with $1.3 million in private and corporate donations, and $800,000 from the state, the center features a museum and an education center and operates as a starting point for tourists visiting area potteries.

Wheel-turned pottery in North Carolina dates to the arrival of the Moravians in the Piedmont in the 1750’s. Farmers needed wares to preserve and contain foods and liquids. So potters produced churns for butter-making, jars for pickling, jugs for vinegar and liquor, and mugs, pitchers and bowls for the table.

While the craft died in most other states during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the agrarian culture and the strong family tradition kept it alive in North Carolina until it found a new market as art. “When the Industrial Revolution catches up to a craft, it usually destroys it, because a factory product is cheaper and probably works better- unless the tradition can adapt to new conditions and changing tastes and find new audiences. That’s what these people were lucky enough to do,” says Charles G. Zug III, professor of folklore and English at the University of North Carolina and author of Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina.

Potters, who once supported themselves by working other jobs, can make a good living these days doing what they love. Sid Luck, a fifth-generation potter, chose to teach high school chemistry when he graduated from college. “There was just no market for pottery,” he says. In 1987, after 17 years of teaching, he quit and opened Luck’s Ware, off winding Adams Road in Seagrove. While most of his offsprings are inexpensive- a coffee mug retails for $5- his volume is high enough that he earns as much as he did in academia.

In the Catawba Valley, on the state’s western side, Burlon Craig’s career reflects how the craft has come to be regarded as art. Craig 84, spent much of his life farming, and working in a furniture factory to make ends meat. He turned pots at night and on weekends. Now his jugs are in such demand that customers take a number to prevent free-for-alls at sales. When he began in the 1930’s, Craig sold five-gallon jugs for 50 cents. In the 1970’s, when he had a storage shed full of unsold pottery, he sold jugs for $6. Today, collectors lucky enough to hear about his annual sale fork over $500 for a five-gallon face jug. (Face jugs are an African tradition brought to the South by slaves.)

When Hewitt first arrived in North Carolina, he packed his mugs, pitchers and planters and lugged them to fairs and a flea market in Raleigh in a quest for customers. These days, buyers flock to his spring, summer, and winter weekend sales. At one sale last year, he sold his entire stock in half a day. Some of his largest pots, 135 pounds of clay decorated with drips caused by melting glass, ash and salt, are snapped up for as much as $3,500.

“I think North Carolina is probably the state that has the longest continuing tradition of pottery as it came to us from Europe,” says Jack Troy, a potter and the author of Wood-fired Stoneware and Porcelain. “If America has a pottery state, it must be North Carolina.”

Over two weeks of traveling North Carolina’s back roads, I dropped in on potters as they prepared for their spring openings. I learned that the tradition continues to evolve. No longer are potters constrained by the types of local clay and glazes. No longer do they learn only regional shapes and forms. Many of the newer potters are academically trained and well traveled, so a range of global styles influences their work.

But the connections to the past remain vital for many, including Hewitt. His father and grandfather had been directors at Spode Ltd., the fine china manufacturer in Stoke-on-Trent, England. But he fell in love with simple utilitarian pots after reading A Potters Book by Bernard Leach, the eminent British potter who helped rekindle interest in early ceramic traditions. Apprenticeships with master potters Michael Cardew in Britain and Todd Piker in Connecticut preceded Hewitt’s drive south to look for a place to set up shop. Near Pittsboro, he and his wife, Carol, purchased a ramshackle farm, transforming the chicken house into his studio and the barn into a rustic showcase for his kiln openings.

Six days after Hewitt and three apprentices closed his fiery monster, I arrive for the unloading, scheduled to begin at 8:30 a.m. The impatient potter, however, had broken into the front of the kiln the afternoon before, taking out a few dozen pitchers and jars. “It looks really spectacular to me,” he says as he starts pulling bricks from the kiln’s side door. Stacked behind the door are the large planters and jugs that fetch the highest prices. They are also the most vulnerable, the most likely to crack or shatter. Hewitt and an apprentice strain to carry out a golden planter with dark-blue streaks down the side. They return for another. “Shoot, that one split,” Hewitt says, stooping inside the kiln. It’s the first big casualty.

Hewitt expects a few disasters. Only about two dozen North Carolina potters fire wood kilns, because it’s so risky. To Hewitt, though, the downside is worth the unique qualities that come only from his unpredictable beast. “There’s a depth to the colors and complexity to the finish that you don’t get from a regular kiln,” he says. As the unloading continues, Hewitt’s spirits rise. A few mugs have fallen, a few small planters are cracked, but the loss is minor.

“The space in the kiln,” Hewitt explains, “is sort of my aesthetic medium. Every single cubic inch can create a different effect.” Pitchers and jars closer to the firebox show drips resulting from ash falling on their shoulders and melting. Hot embers create a mottled charring on vases that have been placed on the floor near stoking holes. Other pots feature gentle flowing streaks down their sides caused by runny glazes and the salt that Hewitt blew into the kiln using a leaf blower. At one point during the firing, he casually tossed mugs of salt through stoke holes onto large pots. The salt melted instantly, flowing down their sides.

Hewitt’s use of salt is an example of how the state’s pottery traditions continue to evolve. Salt-glazed stoneware, recognizable by its orange-peel texture, has been created in the eastern Piedmont since the late 18th century. But Hewitt tweaks the tradition, mixing salt with other glazes for a variety of colors and textures. For example, he applies an alkaline glaze associated with potters in the CatawbaValley that yields a glossy olive green, but by combining salt with it, Hewitt gets a golden yellow. On other pots, he diverts sharply from tradition, using a white Shino-type glaze native to Japan, or a crinkly black manganese slip he created.

His shapes are inspired not only by he simple utilitarian wares of North Carolina, but by the pots he’s seen during travels in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Nigeria, the Ivory Coast and Mali, as well as Great Britain and the United States. “I beg and borrow in a postmodern way,” he says.

Leaving Hewitt and his apprentices to the task of sanding and preparing the pots for sale, I drove to Seagrove. There, along winding Route 705, one pottery sign after another beckons. Pottery Junction, Turn and Burn Pottery, Old Hard Times Pottery, Dirt Works, Frog Pond, Luck’s Ware, Rockhouse Pottery. I pull in at Ben Owen Pottery just across from the Westmoore Family Restaurant.

Ben III, as Owen is called in these parts, is in the early hours of a two-day firing. It’s 3:40 p.m. on a Monday, and the new digital pyrometer that arrived this morning reads 431 degrees. “We’re going up 100 degrees an hour for the first 20 hours or so,” he says. He was up late the night before, putting glazes on the final 50 pots he’d turned over the weekend. He is behind, unable to meet the demand. Special orders jotted on post-it notes are scattered on a wall of his office inside the store, a few feet away. Elton John and Elizabeth Taylor are customers.

If there is a royal family of potters in North Carolina, Ben Owen III is the crown prince. Like many of the young potters in the area, he studied ceramics in college, earning his degree from EastCarolinaUniversity. But he also learned from his grandfather, Ben Owen, perhaps the most famous North Carolina potter of his generation. Ben III was eight when his grandfather started taking him out to the shop to show him how to throw pots.

Pots were everywhere in the Owen Family’s home. Over time, little Ben learned the history of each one. Many bore the stamp of Jugtown, where his grandfather began working in 1923, when he was 18. At the time, the old stoneware shops in the area were closing. Cheap industrial wares had shrunk the market until only a demand for whiskey jugs kept potters in business. With prohibition in 1920, that outlet dried up as well. But Jacques and Juliana Busbee, Raleigh natives, figured they could sell North Carolina pots in a shop they operated in Greenwich Village, New York.

The Busbees opened Jugtown outside Seagrove and hired young potters like Ben Owen, who were willing to try the new shapes that the Busbees believed were key to building a new clientele. They took Owen to museums in New York and WashingtonD.C., and gave him sketches, pictures and pieces of Oriental pottery to imitate. They introduced new glazes, including “Chinese blue,” which became a favorite of collectors. Soon, Oriental shapes and glazes became part of the local idiom. Jugtown remains a rustic mecca today. Buses pull into the lot daily, unloading tourists who browse a small museum and a shop. Vernon Owens, Ben III’s distant cousin, owns the pottery with his wife, Pam. (One branch of the family added an s to the surname.) True to the tradition, they create a variety of utilitarian stoneware.

Jugtown survived because the Busbees fundamentally changed the market. Their customers considered their purchase art, not merely necessities of everyday life. Ben III’s shop reflects that shift; vases, some glazed with his version of Chinese blue, sit atop pedestals illuminated by track lighting. It’s as modern an art gallery as in Soho.

Over two days, the firing behind the store becomes a leisurely social event. Taylor Haynes, world traveler, furniture designer and friend, takes some stoking shifts. LoriAnn, Owen’s wife, keeps plenty of cold water on hand to quench the stokers’ thirst. Owen’s father, Wade, who runs a cattle farm, drops by to tell a few tales. His mother, Shirley, brings dishes from a cookbook she’s writing. Customers wander out to ask questions about the kiln and recall watching Owen’s grandfather turn pottery on a wheel decades ago.

By 2 p.m. on the second day, the pyrometer reads 2,206 degrees. Owen will hold the first chamber of the kiln between 2,300 and 2,500 degrees for the next six hours, a technique called soaking. “You get a lot of colors and effects in the glaze by soaking it,” he adds. If he soaks the pots for too long, the glazes will run. If he doesn’t soak them long enough, they may not develop the colors he wants. Nearly four hours later, Owen peers through the firebox, checking the first row of pots. Before pyrometers, his grandfather checked a kiln’s temperature by monitoring the changing color of the flame at high heat. He also watched the glazes on pots near the firebox, something Owen still does.

Two hours later, he decides to raise the temperature to 2,400 degrees, by feeding more wood to the fire. As the pyrometer clicks higher and higher, friends and family count up- 2,397….2,398…2,399…At 8:01 p.m., the pyrometer reads 2,400 degrees. Owen and Haynes seal the first chamber, then move to the rear of the kiln and begin stoking the back chamber. As they do, flames shoot from ports in the roof and from the chimney. The heat from the open firebox and the exertion are such that Owen sweats despite the cool night air. “It’s kind of like taming a dragon,” he says during a break. “The kiln wants to shoot all this flame out, and you’ve got to control it.” By 9:55 p.m. the dragon has been domesticated. Cones in the kiln are bent to Owen’s satisfaction. He and Hynes close the ports and contemplate on catching up on missed sleep.

When Owen unloads the kiln three days later, the results will be mixed. Several vases crack as he brings them out. Overall, though, he figures the loss at less then 10 percent, considerably better than one earlier firing when he lost about half his wares. “Every firing is a learning session for the next one,” he says.

His pots pay homage to the Oriental shapes that his grandfather made part of the North Carolina tradition, but they also show influences from Owen’s college studies and his travels in Japan. He has made his peace with modern amenities. He supplements wood firings with a gas kiln. And he throws some pots using premixed porcelain, a whiter clay, with glazes that yield vibrant blues, coppers and greens. “There is change,” he observes, “within a tradition.”

Rising early on a gray morning, I drive two and a half hours into the foothills of western North Carolina to meet Burlon Craig at his home in Cat Square Road near Hickory. When I pull up, the door to his shop is open and I see Craig hunched over an electric wheel. He is cranky this morning. His right leg-the leg that held his weight while kicking a treadle wheel all those years- is bothering him. He’s got pots to make and little time for chat, but he agrees to talk while he works.

Craig finishes a milk jug and sets it with others near a rusted stove burning wood in the center of the shop. He walks across the dirt floor to one corner, pulls a ball of clay from a pile and sets it on an old-fashioned scale. Craig and his son, Don, still dig their own clay from a site about 14 miles away, then grind it in a mill out back. That’s a rarity; most potters today order their clay from supply stores.

After reducing the weight, Craig takes the ball from the scale and splits it with a wire attached to his workbench. Then he slams the chunks of clay on the bench, kneading them with thick, strong hands. He repeats the act again until he is happy with the consistency. Returning to the wheel, he wets his hands in a nearby bowl of water and centers the ball with remarkable ease. If the clay is not centered the pot will be lopsided when he pulls it up. He slaps it into place on the first try.

He flattens the ball a little, then lowers a knob attached to a long wooden arm into the center, creating an indentation, and quickly pulls the sides up with his hands. In a minute, Craig has almost magically produced a cylinder about 14 inches high. He thins the walls, slows the wheel and pauses. “I don’t like that much,” he says. “I believe I’ll widen that out.” A few more turns and the shape slowly changes. Suddenly, he’s finished. He uses a piece of wire attached to two pegs to cut the jug from the wheel.

We walk outside to inspect his kiln, which looks like Civil War ruin, though it actually dates to the 1930’s. Craig got his start making pots by helping a neighbor grind clay and collect wood when he was about 14 years old. “Every chance I had, I’d get on the lathe and turn,” he says. After his discharge from the Navy in 1945, he purchased the shop, house and kiln for $3,500.

He’s been turning pottery ever since, though some years, he concedes, he didn’t make much money because he had few customers. In recent years, collectors have come to prize his alkaline-glaze face jugs. Craig made his first face jug in the early 1950’s. These days, he fires his kiln just once or twice a year. Though slowed by age, he still turns every day. “I get tired of sittin’ in the house,” he says. For years, that restlessness was all that kept the alkaline-glaze tradition alive.

The Saturday morning of Hewitt’s spring sale breaks unseasonably cold and drizzly. No matter. Nearly 150 people have lined the dirt road that leads to his farm. Immense, handsome jugs and planters border a path by the kiln. Hewitt has cheekily named one large planter “Monsta V: The Resurrection.” It sells for $2,500. The path leads to the barn, where pitchers, vases, plates, bowls, umbrella stands and mugs are displayed.

Rob Hazelgrove from Raleigh is second in line and not happy about it. “I hit the snooze button one too many times,” he says. Hazelgrove had been first for the last several sales, but Tom Rose of Raleigh arrived at 6 o’ clock to beat him this morning.

A few minutes before 9, Hewitt announces that customers will be led single file down the path to the promised land of pots. “Don’t pass the person in front of you,” Carol adds in a schoolmarm admonition. “And don’t run or you will be sent back.” With that, the sale begins. Customers do their best Olympic racewalk down the path and fan out to claim their prizes. Inside the barn, a long table of plates selling for $40 each is emptied within five minutes. Gone, too, are most of the vases, including some tall, elegant cylinders Hewitt has made for the first time. Veteran shoppers grab first, filling sacks or baskets, then retreat behind the barn to sort through their hoard and do a little trading.

The sale is a sort of reunion among pottery collectors, who eagerly compliment each other on their choices. Cashiers, set up behind tables in an old pasture, ring up the sales. Hewitt works the crowd, chatting with customers who have become friends over the years. He calls his work “high-status functional entertainment,” an acknowledgment that his rural utilitarian pots command urban gallery prices-prices that mean his planters may never hold soil or his mugs an ounce of iced tea. “Potters have an elevated status here,” he says. “I’m preaching to the converted.”

Preaching, that is, to converts like Tom Rose, who grabbed a $650 platter for his wife. And Rob Hazelgrove, who drove back to Raleigh with more than $1000 worth of pottery, including mugs, plates, a vase and a planter. Before he leaves, he tries to explain the appeal of a simple pot.

“There’s something about Mark’s work,” he says. “It just speaks to you. If you buy one piece your hooked.”

-end-

|

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

Travel

Travel

Culture

Culture

Sports

Sports

Environment

Environment

Business

Business

Bio

Bio

Photos

Photos

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog