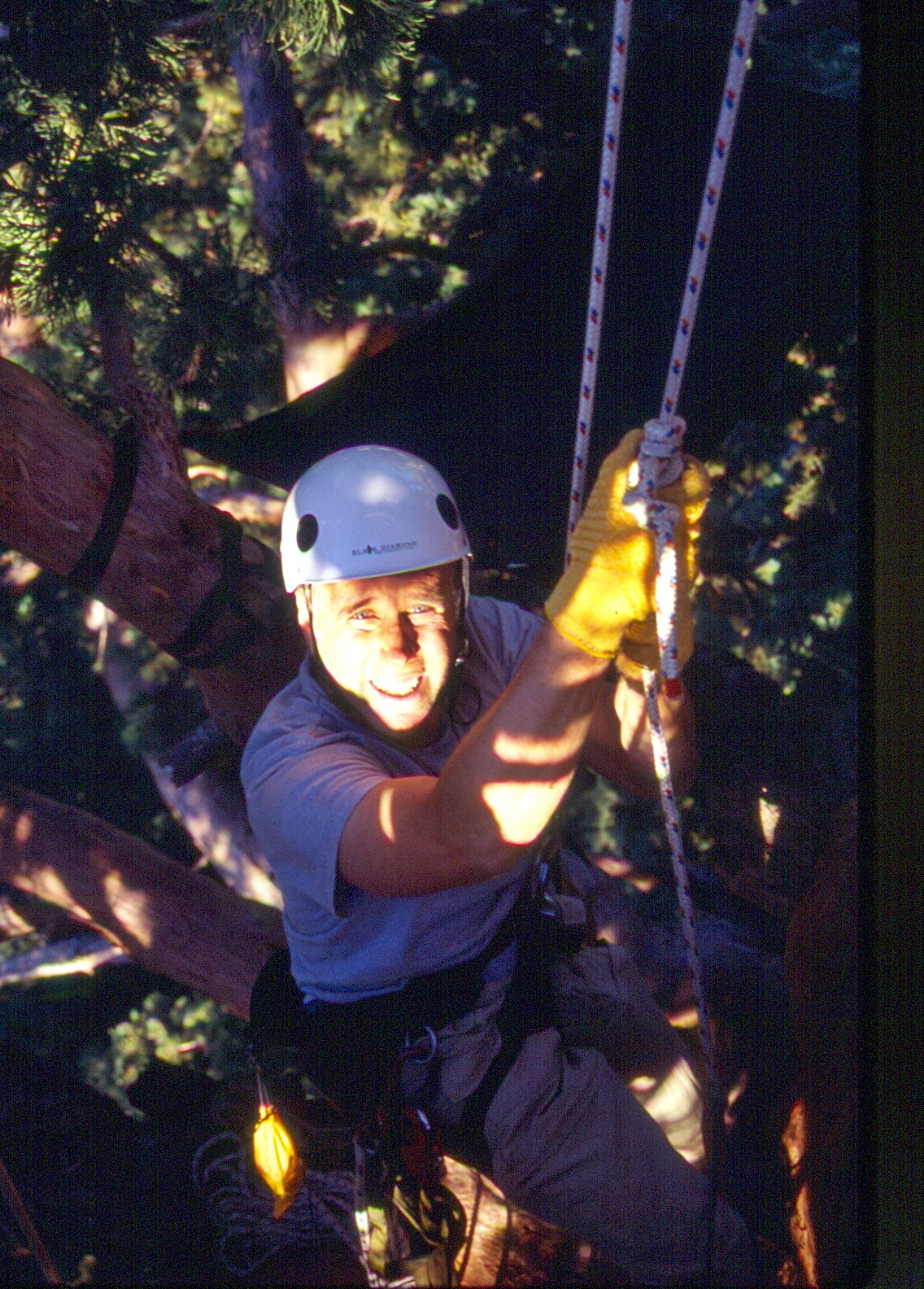

I am swinging from a rope 75 feet high in a giant sequoia, the California mountainside sloping sharply into the valley, creating a vertiginous view only Hitchcock could admire. Looking down is an instant reminder that five million years of evolution separate us from the apes.

I don’t get dizzy, but I do get an involuntary rush, spiking my heartbeat. I’m less than a third of the 243 feet to the top of the Amos Alonzo Stagg tree, the sixth largest living thing on Earth and the most famous challenge -- the Mount Everest -- of serious recreational tree climbing.

While I’ve occasionally gotten into a rhythm, the climb mostly has been a stuttering, herky-jerking up the rope. To my right, Genevieve Summers ascends with the effortless grace of a sinewy ballerina, silently floating through the air. Summers sold her chimney sweep business in 1999 to concentrate on Dancing with Trees, a Georgia company that offers lessons and leads expeditions into trees large and small. She spent the last week as the safety chief and a rigger for a Japanese team that ascended the Stagg two days earlier. But she couldn’t resist a little more tree time and invited me to join her for an overnight stay aloft.

Summers hopes by tomorrow morning I’ll understand why she fell so deeply in love with recreational tree climbing on her first date, an afternoon a decade ago when she took her sons for a trip into leaf heaven at an Atlanta climbing school. "I went up the rope and I just never came down,” she says. “Trees touch me in ways nothing else has touched me. There's an intrinsic connection we have with trees that people know in their guts. People are different when they come down out of trees.”

We’ll see. I’ve got a long night ahead in the Stagg tree to find out for myself.

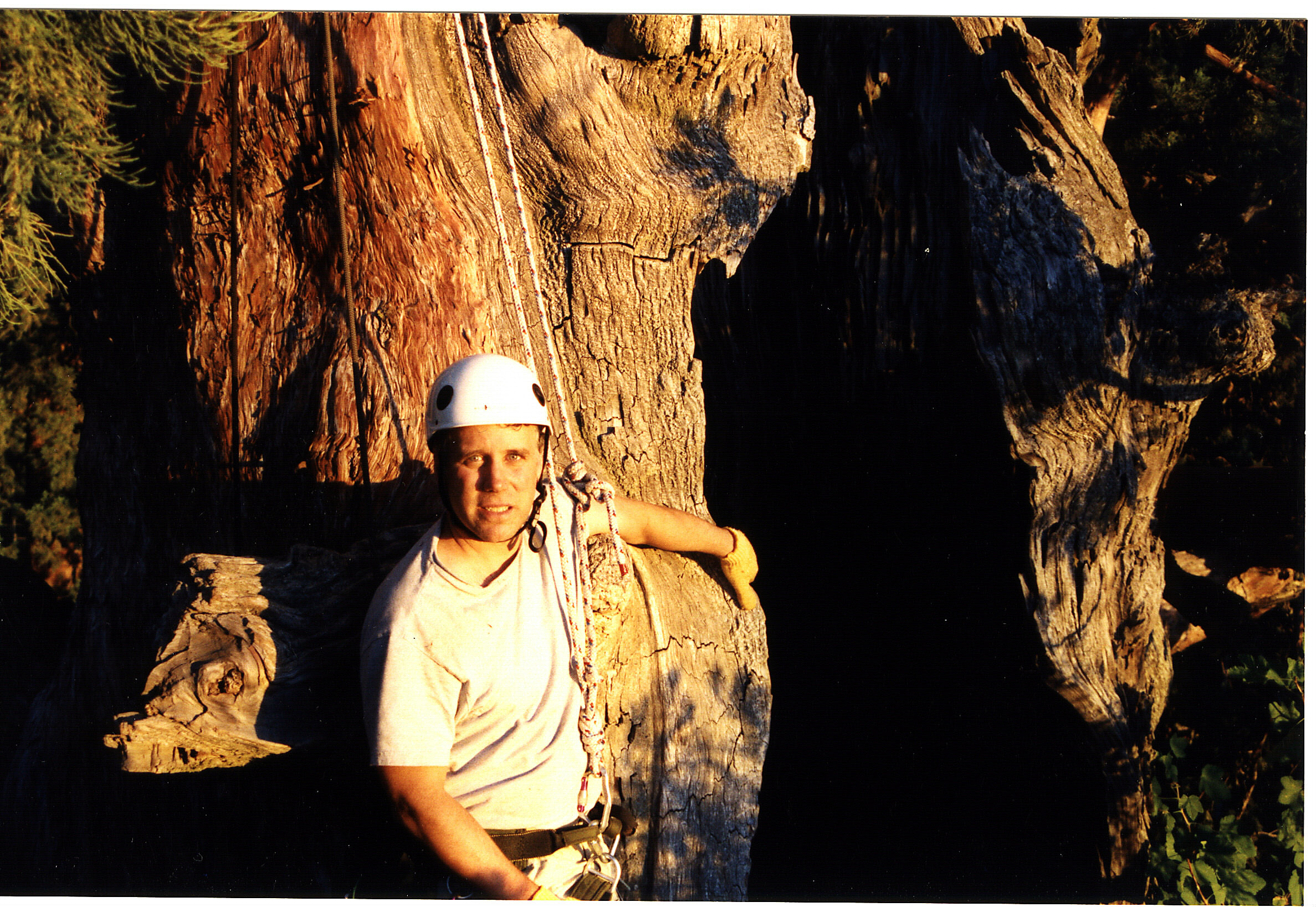

My introduction to Summers and my trip into the giant tree in California’s Sierra Nevadas came courtesy of Peter “Treeman” Jenkins, the Abner Doubleday of recreational tree climbing.

Jenkins is the founder of Tree Climbers International (www.treeclimbing,com), a group of about 600 grownups seriously dedicated to the childhood joys of going out on a limb. From tulip poplars in North Carolina to beeches in England to Baobab trees in Botswana (beware the pythons) they follow the organization's motto: "Get High -- Climb Trees." Several times a year, these modern Tarzans and Janes organize overnight stays, rigging sleeping hammocks called "treeboats" between branches high off the forest floor.

I’d called Jenkins in Atlanta earlier in the summer to ask if he planned any tall tree climbs and he suggested I join him in California. It was a rare opportunity. Scaling redwoods in national parks generally is prohibited. But this climb would be on private land and had been approved by the owner, with the proviso we sign a waiver of liability in case of death, of course.

For Jenkins, the week promised to be a reunion of his disciples, people who learned their climbing techniques at his school in Atlanta, and have gone forth to spread the word. For me, it was a chance to understand not only what they do, but why they do it.

Jenkins is credited, rightly or wrongly, with inventing recreational tree climbing. He's part absent-minded professor, adrift without his Palm Pilot, and part impetuous boy, probably a necessity for throwing a rope over a limb and pulling yourself into a tree. He's climbed trees in parks, hauled his ropes up behind him and barked as clueless strollers ambled by, looking vainly for the offending dog. He's hung out on a limb and exchanged hoots with owls. He's scaled a 357-foot coastal redwood.

In 1978 he was visiting his parents in Dallas when an ice storm broke limbs on trees across the city. Jenkins had just been rock climbing in Estes Park, Colorado. One look at his equipment and those damaged trees and he decided to become a tree surgeon, though he had no training. Why not? It looked like fun. In 1978 he was visiting his parents in Dallas when an ice storm broke limbs on trees across the city. Jenkins had just been rock climbing in Estes Park, Colorado. One look at his equipment and those damaged trees and he decided to become a tree surgeon, though he had no training. Why not? It looked like fun.

After returning to Atlanta and hearing from client after client that his work looked more like fun, he began offering free lessons two Sundays a month on a sliver of land with a pair of 100-year-old white oaks. Soon, they had names – Dianna, the graceful one, and Nimrod, the muscular one (his ashes will go into a hollow at its base). "We name all our trees," Jenkins says. "It's a very personal relationship."

Over the years, recreational tree climbing has evolved, borrowing tools and techniques from arborists, cavers, rock climbers and Robin Hood (ropes are placed in tall trees like sequoias using a bow and arrow). Climbers strive to leave the tree unharmed. Gaffs -- leg spikes -- are prohibited. Ropes are placed carefully so they don't cut into branch crotches. "Cambium savers" -- straps or pieces of flexible pipe -- go over the back of the thin-skinned branches of sycamores, beeches and maples to prevent damage. Locations of favorite trees aren't publicized to prevent their overuse. "Ethics are very important," Jenkins says. "You can kill a tree with too many climbers and the wrong climbing technique."

TCI's membership skyrocketed in the late 1980s when essayist Robert Fulghum declared himself a dues-paying, card-carrying member in his bestseller, "It Was on Fire When I Lay Down On It." Fulghum later narrated a video about tree climbing, "Tickle the Sky," likening the life-changing perspective of going up in a tree to Henry David Thoreau's time at Walden Pond. Climbers are fond of quoting Fulghum’s Zen-like pronouncement that tree climbing "is an attitude, a place to be, rather than something to do."

To enthusiasts, it's not important how high you climb. "A lot of people assume that it's a thrill sport or a test of physical athleticism, but it's really not," says Sophia Sparks, whose Oregon company, New Tribe, creates climbing saddles and other gear. "There is certainly a huge thrill to be up in some of the tallest, oldest trees, but you can get the same rich, warm feeling from even your backyard apple tree. What I find is as soon as I leave the ground, I leave all my troubles behind."

About 100 feet off the ground, feeling my tree legs, I begin to understand what she means.

”Want to do some tree dancing?" Genevieve asks. By now, I trust the equipment. We push off from the redwood pillar and become pendulums, our child-like cries of "Wheeee" changing in pitch as we swing.

On our way up, we've found a hollow in the trunk called the refrigerator that blows cooling air. We've watched the bark transform from spongy, two-foot thick cinnamon at the base, which protects against fires, to the harder, thinner mottled gray, auburn and tan bark higher up, resembling something Van Gogh might have painted. Oddly, the higher we climb, the more comfortable I become.

As we rise above the rest of the undulating canopy, it’s impossible not to be moved by its majesty and permanence of this tree, which is probably 2,000 years old. Cherokees called sequoias the “Ancient Ones” and prayed for them to pass on the knowledge of earlier generations.

One hundred years ago, John Muir labeled the Sequoiadendron giganteum “the Auld Lang Syne of trees.” In his book, “Our National Parks,” he described them as "lonely, silent, serene, with a physiognomy almost godlike… As far as man is concerned they are the same yesterday, today, and forever, emblems of permanence."

After 90 minutes of climbing and becoming comfortable with the view, we reach our room for the evening. Actually, a more accurate description is that we’re checking into the world's smallest and highest natural cathedral, a gnarled sculpture of dead wood 240 feet atop a tree 6,500 feet high in the Sierra Nevadas. The Stagg's top has been blown out, perhaps by an ancient lightning strike or windstorm, creating a hollow protected on three sides. A "door" opens to the west framing a view that is both commanding and humbling, a ridge in the near distance and the sun beginning its solemn afternoon descent.

We pull our sleeping bags and gear up a haul line and stow them in the cathedral. Then I join explore with Genevieve, who has set up her treeboat and is moving confidently from branch to branch in bare feet. I think back to what Peter Jenkins told me the first time we met. "Whether it's old software from when we used to live in the trees, I don't know," he said. "There is something about being in the crown of the tree. You get quiet. You get peaceful. You get happy. Your worries are gone."

It is also deeply moving, a reminder of all that trees symbolize – permanence, shelter, strength and beauty, especially beauty. Climbing an ancient survivor like the Stagg tree is more emotional than physical. It’s an indescribable wow, that feeling of being part of something greater, of stepping into an eternal moment. It’s like watching a child come into the world. Or seeing a Titian painting in a Venetian church for the first time. Or, as I had done years earlier, hiking into the mountains of Mexico to visit the winter sanctuary of 150 million monarch butterflies.

Summers knows that ineffable feeling. For her, climbing has been a spiritual calling since her first trek with Jenkins a decade ago. As a chardonnay sun dips near the horizon, she invites me to sit on a thick branch and read from "The Attentive Heart: Conversations with Trees," essays by Buddhist environmentalist Stephanie Kaza. I’m dubious, but it seems worth a try.

The breeze has come up and, as she looks for a selection, the wind makes a choice for us, unfurling the pages to the title essay. "All night, " Kaza writes, "the trees have been conversing under the full moon, weaving me into their stories, capturing my dreams with their leaning limbs and generous trunks. Breathing together as I slept, as they rested, we danced quietly in the summer night."

The wind catches the pages again, spinning them closed, as if to say words aren't necessary now. We sit, listening to the breeze murmuring through the needles, the giant tree occasionally groaning softly beneath us as the sun dies behind the ridge. The wind catches the pages again, spinning them closed, as if to say words aren't necessary now. We sit, listening to the breeze murmuring through the needles, the giant tree occasionally groaning softly beneath us as the sun dies behind the ridge.

In the dark of the cathedral, we eat by miner's lamps, sharing children's favorites -- peanut butter and jelly and apples -- and the eco adventurer's staple -- PowerBars. We turn in locked to our ropes, a comforting, if not comfortable, requirement. Sleep visits only occasionally so I watch the night sky transform from a milky lavender and gray to a matte black sprinkled with countless stars. I’m in a place before time, before history, another in an endless line of men alone in the forest quiet.

Deep into the night, the wind picks up and I wonder if weather is blowing into the mountains. Genevieve had mentioned a "hairy" descent from the Stagg tree with her sons a year earlier in driving rain and falling temperatures. But the wind fades and the morning clear brings a visitor, a lone bee that somehow has found its way to the treetop.

After breakfast, Genevieve teases me into trying her treeboat, an experience akin to surfing a hammock 220 feet above the ground. “Kind of wicky wacky, isn’t it?” she says as I haltingly lower myself. My brain knows I’m tied in and won’t fall far. But my body isn’t so sure. The first time I step onto the unstable surface, I feel that involuntary adrenaline rush and the spastic desire to grab onto something solid nearby. Once again, fault those millions of years of evolution.

Soon, it's time to leave our cathedral. I'm tired and ready. My reserve of nerve is running low. All week climbers have told me that the descent is the most dangerous part of the sport. To reach the ground, we clip into a rappel rack, a device that supplies friction to the rope, allowing a controlled drop. Thread the rope through the rack incorrectly and there will be no friction; I'll plunge 240 feet in seconds. No one can recall it happening -- there's an "idiot bar" to guide you -- but that doesn’t make me any less nervous. More likely than threading the rope wrong, is the possibility of descending too fast and losing control.

Neither happens. I thread the rack right the first time, passing Genevieve’s inspection. We slip slowly through the crown of branches and soon -- too soon -- the ground nears. I linger at 100 feet to enjoy the valley view, then at 50 feet for one last pendulous dance.

I'm reminded of the first time I went climbing in Dianna one Sunday several years ago with Peter Jenkins. That afternoon, I joined a dozen members of a Girl Scout troop. There weren't enough ropes for all of them to climb at once. When someone on the ground asked who was ready to come down so others could go up, the answers were immediate.

"I'm not."

"I'm not."

"I'm not."

I'm not either. Not this morning.

Genevieve was right. People are different when they come down out of trees. In more ways than I could have imagined.

|

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

Travel

Travel

Culture

Culture

Sports

Sports

Environment

Environment

Business

Business

Bio

Bio

Photos

Photos

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog