| ![]() | |

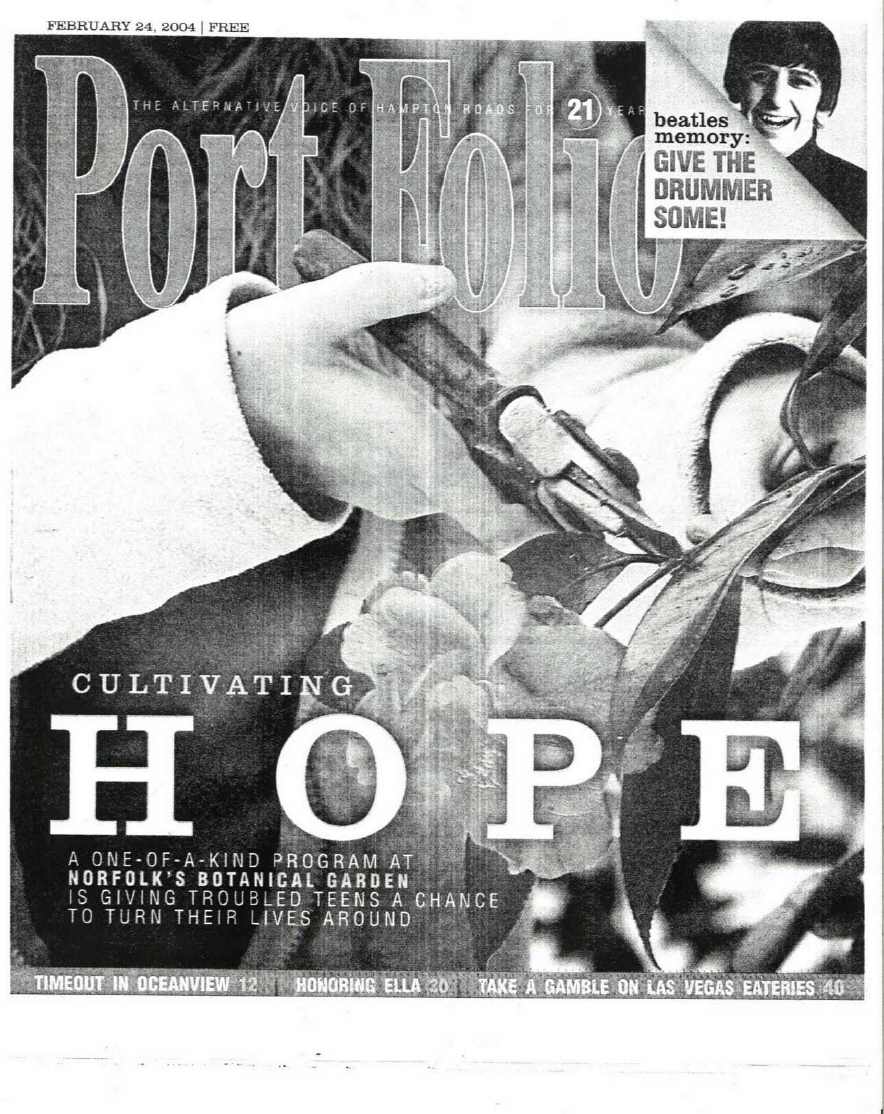

| From Port Folio Weekly |

The names of juveniles in this story have been changed.

Monday, October 20

It's the first day of the last-chance school, an unlikely sanctuary at the NorfolkBotanical Garden for troubled teens struggling to break the downward spiral of problems at home, failures in the classroom and scrapes with the law.

Inside the cramped office -- four desks, one computer -- of the Horticultural Enrichment and Learning Program (HELP), the fulltime staff of three is checking on the kids they'll pick up over the next hour. Several are repeaters, youths who did well, but the staff thought needed more than the usual 10-week program, a unique hybrid of vocational counseling and classroom instruction run by the gardens and Norfolk's Juvenile Court Service Unit.

On this Monday about 7:45 a.m., Mary K. Scott, the horticultural therapy program manager, dials one of them, a boy named after a weapon.

She has a soft spot for this star-crossed child, who watched his mother vomit blood and die from alcohol poisoning about nine months earlier, seven years after his father took one last heroin ride. He always looks like he's been crying, a tender perennial wilting inside. He'd responded his first ten weeks in the program, slowly surrendering to her grief counseling, embracing the gardening chores and challenging himself in the GED class.

Scott is a veteran of places as tough as the BrunswickCorrectionalCenter, where she counseled convicts; the Newport News Juvenile Justice Department, where she was a parole officer; and a hospice in the Florida Keys, where she helped people suffering from cancer and AIDS die. At HELP, she's found a way to combine her love of gardening with her talents as a counselor. She's tanned and sinewy, tough on the outside and both tough and soft on the inside when she needs to be.

She reaches him by phone, just to make sure he'll be ready for the industrial white van that meanders through the toughest sections of Norfolk, ferrying children to the garden. And he explains why he won't be coming this morning -- or any morning soon.

He walked in on his sister Saturday evening lying on the couch. She was dead, the needle that delivered the numbing, fatal dose of heroin still dangling from her arm.

Scott just wants to hold him, tell him it's not always going to be this bad. She wants to tell him he will be happy from now on. But she knows his experience says otherwise. For him, life isn't what it's like for most kids. So she tells him that his sister suffered from a disease, that she didn't want to leave him. And she reminds him what a support his stepfather has been.

Then it's time to pick up those who will be coming. Joshirlon Hargrove, the HELP coordinator who has also been on a call about the death, leaves her desk and walks out to the van with Kenneth Traynham, an ex-Marine new to the program. They only have seven youths to pick up. They'll be more as the fall progresses, more kids who realize they're not going to finish school and agree to transfer into a program that will help them get a GED.

Going door to door, the two HELP counselors pick up the fall class. Levon* hops on and moves straight to the back, but not soon enough for his shiner to escape notice. Just wrestling with one of his boys, he says. Renaldo* pops in and Traynham asks him about his upcoming basketball games.

In decaying Grandy Village, Traynham has to honk twice before Sondra* appears in the doorway. She slow walks, head down, a trademark of girls her age in this neighborhood, the 30 feet to the van, moving with infuriating deliberateness oblivious to the waiting adults.

Five minutes later, Eleanor,* the Goth kid, strides more quickly, then discusses why she quit her dead-end job, breaking the halted conversations Traynham had started with the boys about sports. In Ocean View, Joe* rolls his shoulders as he walks, ambling into the van. When Patty* steps into the van from the sidewalk on East Ocean View Avenue, the conversation becomes her monologue about a weekend excursion to watch the battle of the high school and college bands.

All of them are two or more years behind in school. Some are on probation with the Juvenile Court.

Joe is 17 and would have started the seventh grade -- again -- last fall. He also has a two-page rap sheet of marijuana possession, breaking and entering and petty larceny, rip-offs, Scott says, to help support a mother battling cocaine use and addiction to painkillers. He completed the program before and was up for a job as an arborist trainee with the garden, but flunked the urine test.

Eleanor, also 16, would have been in the 9th grade again after missing more than 40 days the previous year when she got pregnant and later endured a miscarriage. Her mother suffers from mental health problems Her father, whom she hates, moved away when she was very young then came back and moved in and out of her life over the past nine years. He was abusive, she says, until she finally hit him back one day.

Earlier in the year, he had moved back into the house with her mother -- and her mother's boyfriend and her grandmother and a brother fathered by the boyfriend. Then her boyfriend moved in with her family because his father went to prison and his mother moved away. But Eleanor's boyfriend and her father fought constantly. After a dispute with her mother, police stopped her as she was walking away from home. There was a scuffle and she was charged with resisting arrest. She wants to be emancipated from her family and study to become a mortician.

Lorenzo was pulled from his family, including two sisters and a brother, when he was seven after his mother lost custody because of a drug problem. The children moved into different homes; he went into foster care. When he was 13, his mother got custody back. He got caught stealing earlier in the year. He's 16 now and would have been in the seventh grade.

Sondra, the slow walker, is 16, a truant who would have been in the seventh grade. She lives with a mother who is often at work.

Levon, a 17-year-old repeater in the program and a favorite of Scott's, is a truant and a runaway who hates school, though he's completed the ninth grade. He got kicked out the last time, he says, for telling a girl she was fucked up. He loves bonsai. But once he starts to go off, Scott says, he can't control himself.

Justin, 17, got pinched for cocaine possession. He lives with his mother and has been in the Norfolk Juvenile Detention Home. He hates school and would have been in the 9th grade -- if he went to school.

"They're all the same kid," Scott says. "They don't fit anywhere. Get 12 of them together and they're all the same. They act like a family."

When Ed Bradley, a now-retired Norfolk Juvenile Probation and Parole officer, came up with the idea in 1997, he discovered the garden was a place not only for vocational training, but to get inside the distant, distrustful facade so many of these kids have erected over years. "This," he says of the garden, "is the best place I've ever done counseling."

"Bringing them here opens the door for us to get in there," Scott adds.

Often, Scott pulls aside someone for one-on-one counseling while the group is working in the garden. Or a counselor like Traynham or Hargrove will sidle up as they're walking to a job and ask about what's going on at home.

The task this Monday morning is making scarecrows in the vegetable garden, a short walk from the education building where the program has a classroom. Sondra slow walks all the way there, despite urging from Traynham to pick up the pace.

At the vegetable garden, the group moves into manufacturing with degrees of enthusiasm. Eleanor, of course, takes the pillowcase used for the scarecrow's head and draws a vampire in black and white and red. Joe quickly creates a scarecrow nattily attired in an orange sweatshirt, then decides he's too stuffed and tears him apart and makes another. Meanwhile, Scott sits in the gazebo with Lorenzo asking him about what's going on in the neighborhood, softly encouraging him not to do what the other kids are doing.

With some youths in the program, she says, it takes weeks to get them to begin talking. The changes are subtle, achingly incremental. "It's a smile where they used to look down," she says.

What is success with kids like this, Scott wonders, kids whose lives have been so deeply dysfunctional. "I can't change lifestyles and upbringing in ten weeks, but I can give them a safe place to go," she adds.

Tuesday, October 28

Terrance Afer-Anderson, a sex education counselor from the Norfolk Department of Public Health, runs a rap program each Tuesday morning during the program. He greets the bleary-eyed crew by joking that "I'm Dollar and my son is 50 Cent." Only Joe chuckles. He's acquired a black eye. Scott and the other counselors are dubious of his explanation it came from a piece of flying concrete at his job.

Afer-Anderson tells them he became a father at 18 to a son who died four months later. He talks about how hard it is to have a child when you’re still a teen. The group listens impassively. There are a couple of new kids since last week, including Renaldo*, who wears the usual guy outfit of a XXL hoodie and oversized pants with the belt loops circling his upper thighs.

During his hour, Afer-Anderson has them answer an extensive survey about their attitudes. They are asked if it's important to:

-- get an education.

-- get along with parents.

-- have a romantic relationship.

-- have sex with someone I love.

-- do well in school.

-- not have sex until I'm married.

-- wait to have children until I'm ready to raise them.

-- use protection every time I do have sex.

"Do we got to answer this?" Renaldo asks.

Afer-Anderson pushes on.

They're asked if they agree or disagree:

-- my boyfriend or girlfriend would help out with a baby.

-- my parents would be supportive if I had a baby while still in school.

-- I could still have a successful career if I had a baby now.

-- postponing sex until I'm older will allow me to finish my education.

-- waiting until later to have sex will make me a better person.

-- if a girl gets pregnant, it's her fault.

There are more questions, including a set about anger management. They dutifully scribble their answers.

Then it's out to the vegetable garden to weed and pull dead vegetables, including some cherry tomato bushes still full with fruit. For a while, half of them watch while the others toil. Joe, who is nicknamed "John Deere" for his enthusiasm getting into the dirt, and Levon lead the work, pulling out tomato plants. Hargrove encourages Lorenzo to get involved, but he ignores her. He didn't play in his basketball game because his back was hurting and he's as downcast as the gray, cool, threatening weather this morning.

Eventually, nearly everyone pitches in, with a new girl, Kathy*, joining Eleanor on their knees to pull weeds. Eleanor, Joe and Patty wear their green, H.E.L.P T-shirts.

After lunch, Richard Hazelette, the program's GED preparation tutor sweeps into the room and writes on the board:

Bonanza

Hype

Ballyhooed

Surpassing

Coronation.

They're words from a newspaper story about LeBron James he distributes. He asks them to pull out the dictionary and find their definitions. All except Sondra begin paging through the thick paperbacks on each table. She sits sullen, arms inside her sweatshirt, leaning back in her chair.

From there, they move on to the proper use of the possessive. When Hazelette goes to check homework, he learns that none of them have done it. The GED, he notes, isn't easy. It's a long, hard test. "You have to have a burning desire," he says. "It's not going to hurt me. It's going to hurt you. It's going to possibly delay you getting that GED and moving on."

Two weeks later, they take a Thursday field trip to the

VirginiaMarineScienceMuseum (Thursday field trips are rewards). Three of them -- Levon, Lorenzo and Patty -- are left behind at the garden because they did not do their homework the day before. So Hazelette is getting results from most of them.

Monday, November 17.

Three new participants, David,* Matt* and Dorothy,* have joined the program. In the past, HELP began with 12 students and generally two or three each session were dropped. It made the group cohesive, more like a family, Scott says. But the court service unit, which oversees the program, wants the 12 slots filled at all times so the program has been adding students as they become available. That means the counselors this session face a roster that can change from week to week. Scott doesn't like that and she will later decide to go back to the old way beginning with the April session.

David was home-schooled by a tutor supplied by the public school system because he suffered from anxiety problems. Matt, a non-stop talker and joker, entered after missing too many days of school in treatment for bone cancer. Dorothy, another withdrawn slow walker, started the school year skipping too much and was placed in the program.

The vocational lesson this morning is about making cuttings and rooting them. As the teens slice begonia stems, Scott makes a point to praise Renaldo. Later, Traynham takes him aside to talk about his family.

For their garden work, the group has a new regular supervisor, Petey Kitzmiller, whose enthusiasm is unwavering. 'Hey, sugar, do you want to do some digging?" she says to a sullen Dorothy in the perennial garden. "I can tell you're a digger."

Dorothy and Justin work dividing flowers in one part of the garden while David, Renaldo, Eleanor and Kathy carefully spread mulch in another area.

At lunch, it's the usual fare. Eleanor has Doritos, Cheese Curls and a Sierra Mist. Renaldo goes for two sodas -- Sierra Mist and 2 Mug Root Beer as well as Doritos and fries with cheese, nacho bean sauce and ketchup. David doesn't have money or something from home so he opts for micro waved flautas from the program's refrigerators and pronounces them "nasty." Most of the others have fries and soda, too.

As Hazelette teaches a session on rounding numbers after lunch, Hargrove and Traynham are on the phone with Renaldo and his mother. On the previous Thursday, he and Levon "bucked," as counselors say, and refused to work. He faces expulsion. But he's apologetic. At his mother's urging, he agrees to come back and work every day.

"Kids want to come here," Scott says. "They tell their friends and their friends call me and ask, 'Can I come?"

Tuesday, November 18

While Afer-Anderson is showing a video about teen pregnancy hosted by Leeza Gibbons, Scott is in the office talking with Levon, who is repeating the program. "You know you're like a kid of my own to me," she tells him. "I'll talk to the counselors about it. But the thing is the other kids are watching what you do."

She’s especially fond of him, calling by his full name and kidding with him often while he works in the garden. When she's around, he's fine. When she's not, he defies the other counselors. And his defiance sends the wrong signal to the others.

She's providing Levon with a soft place to land. He will be terminated from the program.

After her phone call, Scott goes into the classroom, sidling up to Kathy. "I know you're happy to be here," she tells her. "You're just looking miserable.

The day's work is dividing and potting irises, carex and other perennials at the garden's garage area. Once again, Joe takes the lead with David, working at a table filled with thick roots that need to be split. The rest join in; there's less standing around than weeks earlier.

Sondra has her black jacket wrapped around her shoulders, but she's wearing her green HELP T-shirt. And she moves quickly when Petey Kitzmiller tells her to begin organizing the repotted plants in rows. There, Carol, another relatively new participant, straightens the rows and helps David count the number of each perennial. "You guys are this big green team," Kitzmiller tells them.

But one student, Lorenzo, remains distant in the midst of the work and the kidding. Sunday, he tells Scott, was his birthday. His mother forgot.

During the GED class, Scott slips out and buys him an ice cream cake with his name on it. When she enters the classroom with it, his eyes light up. "Did you know I don't like regular cake?" he asks.

He cuts a piece for everyone else before taking one for himself.

"You tap into what's been shut off," Scott says later about that day. "They put these walls up where they're not able to feel anything. They can't fee anything bad, they can't feel any joy either."

Thursday, December 4

The counselors show the group the movie, "Antwone Fisher," the story of a troubled youth with a violent temper and a history of physical and psychological abuse. As the movie runs on, Lorenzo begins covering his head with his coat. Afterward, he gets angry. The next day, he doesn't come.

But he calls Scott and apologizes: "That movie messed me up. That was my whole life story," he says. "I was real pissed off and I didn't know how to tell you what I was feeling."

Sondra doesn't see the movie. She cut days earlier in the week and Hargrove suspended her, then called her mother to tell her she was adding three weeks onto the program because of days she'd missed. Sondra agreed.

"That's their background," Hargrove says. "They go to school. Then they skip a few days. We have to get them out of that habit."

Trusts build slowly between individual counselors and students. Hargrove has become Sondra's shoulder by learning that she can't push too hard. She asks her how she's doing, gets the brush-off, and backs away.

Sondra is slowly buying into the program. She’s working harder. She even admits to liking flowers now. "This program will work for her," Hargrove says. "But she has to work for it."

"A lot of these kids have been to counseling. Family counseling. Drug counseling. They don't really like counselor," Hargrove adds. "They see counselors as being in their business, trying to get into their head. They only need counselors if they're crazy and they're not crazy. So I just treat them like teenagers. I tell them I don't treat them any different than I treat my nieces and nephews.

"What these kids want and need is just to be treated like regular people."

Tuesday, December 9.

The morning features a "Jeopardy!"-style game staged by Afer-Anderson about sex education and the kids show they've been listening. They supply questions to answers about subjects like HIV, herpes, anatomy and pregnancy. The answer, "typically four to six inches in length when erect" draws a laugh from Matt in the back. But, for the most part, they take the competition seriously.

Work today is in the butterfly garden, where they pull annuals and trim back perennials. Hargrove has to push Matt and some of the guys to get to work.

Joe is agitated and moody. It turns out he partied over the weekend and is worried that he won't pass the upcoming urine test for the arborist's training program.

As she's working, Carol tells a counselor that "I'm just a whiner; it's a habit."

A few days earlier, Scott brought her back from a garden job in the golf cart, a favorite way for her to get some one-on-one counseling time. Carol, a truant and runaway, told her she was suffering from an anxiety attack, having trouble breathing. They practiced some deep breathing and yoga.

Slowly, Carol began to talk. Her mother had two older daughters when she married her father, who molested them over a period of years. Finally, he went to prison.

But the sisters blame Carol, who was not assaulted, for being the reason their molester came into the family. "She lives in a house of hate, " Scott says. "She would love to talk about it and express it, but she doesn't know how. "

Scott gave her a composition notebook and reads what she writes once a week as a means to begin counseling. The themes are familiar. "As we peel back the onion, we'll find domestic turmoil." Scott says. "That's the kid we get. The red flags are court involvement, school drop out. But the family is at the core."

It begins to rain as the work session finishes in the butterfly garden and the group hustles on the long walk back to the building. There, Hargrove reads them the riot act. Scott calls her the "big mother, the tough mother."

"For those of you who were working, thank you," Hargrove says. "For those of you who I have to ask three or four times to do something, that's not working. You have to come here and do what you're asked to do and if you can't do that, we have to find another place for you to be."

Thursday December 11

The weather is too foul for the scheduled field trip to the Cape Henry Lighthouse so Scott decides to hold her grief and loss counseling session.

She has the group arrange their chairs in a circle and they begin talking. Many of them lost a loved one to death. They also deal with grief and loss in other ways. They've lost a parent to drug addiction or to the penitentiary or to a divorce. Only one of them lives with both birth parents.

Scott begins the session asking each of them what they think happens when you die. Several say they never talk about it. A couple of students say we come back and try again to get it right. Another says the maggots get us.

Then Matt talks about how he felt pain in his hip and soon was talking to doctors who told him the cancer was so bad he might not make it through to the morning. "When I woke up and saw that I was still alive, I decided to fight," he tells them, teary-eyed. “I wanted to live.” A couple of students hug him.

Meanwhile, Justin has turned his back to the circle. He's despondent. Scott and the other counselors can't get him to explain why, other than it has to do with a grandmother. Traynham takes him home early.

Monday, December 15.

It's the last week and students have been typing resumes and their letters to the

Norfolk school system seeking permission to take the GED (you have to be 18 to take it without school system permission).

But this afternoon they hear a talk from Deirdre Brown of Empowerment 2010 about interviewing for jobs. The advice is basic to most people. Not them. Dress well. Make a good first impression. Ask a few questions. Follow up with a thank you note.

Then she asks for volunteers to practice before the class. No one volunteers. "Somebody go up and do an interview, " Hazelette pushes. "(David) go for one. Firm handshake, look her in the eye."

David picks up his resume, walks to the front of the room, hands it to her and say, "Hey."

That's it.

She's patient. First, she says, don't say 'hey.' Give your name, even if they have it.

Take two:

David walks up, shakes her hand and introduces himself.

"Tell me a little something about you," she says.

"I don't know what to say," he responds. "I play guitar and draw. I know how to plant trees and stuff."

The interview, though halting, moves on from there. David, the student with anxiety attacks so severe he can’t attend public school, has completed a mock interview in front of the class. Hazelette leads the applause as he returns to his seat.

Next up is Eleanor, who is poised, firm and communicative. Brown says she is looking for someone to read to children and Eleanor tells her she has a younger sister and a younger brother, that she goes to the library and that she enjoys writing and reading. Brown praises her effort.

Then it's Justin's turn. He swaggers up, introduces himself but when Brown asks him what he does, he says, "Me and my homeys just chillin'." She stops and suggest he "think proper English" when being interviewed then goes on to ask him about his experience. He says he's looking for a dishwasher's job. She tells him the only opening is for a waiter. Would he be willing to learn? No, he says. Dishwashing is what he wants. Brown says she'll call if something comes open.

Wednesday, December 17

The day before graduation, Scott, Hargrove and Traynham advise the students about what to what to wear. No miniskirts. No baggy jeans. "I don't want to be wearing that tight stuff," Matt protests.

Then Scott asks them what the program has meant to them. "It meant nothing," Dorothy responds. "Ok," Scott says, "we'll pass on you."

Eleanor says now that she's completed the program she's going to get a job and save for college.

"I want to be a hard-working man now," Lorenzo says.

"I'm proud that I'm just about done with the program and I'm going to get my GED," Kathy says.

"I don't know," Carol says. Scott asks her about her favorite staff member or her favorite field trip, trying to draw her out? Carol just shrugs.

Sondra, too, refuses to answer, shaking her head.

Finally, Dorothy is ready. "I'm proud I almost finished this program," she says.

Thursday, December 18, Graduation Night

Eleanor shows up early for the 6 p.m. graduation with gifts -- small teddy bears -- for the counselors. She's wearing heels, a blue sweater and a long black skirt though she also has the black nail polish of her Goth days.

Kathy is there with her mother. She plans to go to beauty school. "They've done wonders with this one," her mother says. "She's a completely different person."

Scott says hello to Renaldo's mother and tells her: "We're trying to get him a job here." When she gets a puzzled look in return, she asks, "He didn't tell you?"

"No," says his mother.

When it comes time for the students to talk, only Sondra, the once-sullen slow walker, strides to the podium in a shimmering blue dress and heels. She's here with her boyfriend; her mother hasn't showed. She's poised, confident, thanking Hargrove for keeping her focused and Traynham for helping her with her "man problems."

"I've never been so happy in my life," she says. "To the other students, congratulations and let your dreams and hopes become successes."

POSTSCRIPT

Six of the students pass the pre-test for the GED and are ready to take it, an unusually high number. One of those is Joe, who in a previous session made little progress. But this time he worked, even coming in on the optional Friday some weeks. “Overall, his attitude just got much better and that made the difference,” Hazelette says.

Over the years, Hazelette, who has been the HELP tutor since the first day, says more than 40 students have gotten their GEDs over the years.

Months earlier, Eleanor had written in her journal a poem titled, “Dead or Alive” that ended with the lines:

“I lie awake at night, tossing and turning, wondering

whether someone could ever love me

whether I will die alone or with my true love

I lie awake at night, tossing and turning, wondering

If I’m better off dead or alive

If I’m better off in heaven or hell

But all the answers are simple: Dead and Lonely!

Now, things are better at home. She plans to earn her GED and study to be a mortician at

TidewaterCommunity College.

Scott encourages Joe, Renaldo, Lorenzo and Carol to apply for the garden's arborist training program. Renaldo doesn't show up for the interview, claiming there was a shooting outside his home that kept him up late. Traynham says he's worried about him. “Some days he comes in and he’s fine. Other days he comes in and he doesn’t talk, he doesn’t do anything,” he says. “It’s a constant struggle with him.”

Joe and Lorenzo both ace their interviews, pass the drug test and become the 25th and 26th graduates of the program to get jobs at the garden. Lorenzo, Scott says, is coming out of his shell thanks to the job. "I think it's going to change his life," she says.

The staff re-enrolls Sondra in the program because she hasn't written the letter requesting permission to take the GED. But during January she begins missing days. Hargrove terminates her. Sondra arrives one day with a boyfriend and demands to be reinstated. Then she goes off on Hargrove, screaming obscenities.

Matt, Levon, Dorothy and Patty call occasionally to talk with the counselors. Patty has enrolled at

TidewaterCommunity College. Levon and Matt are back in high school, where they hate it. They want to return to the program in the spring.

Carol comes to see Scott the day after graduation to tell her that she's pregnant and her mother won't help. She needs some vitamins, she says. Her boyfriend plans to enroll in the Navy, she adds, so they'll be ok because he'll get benefits. Scott asks if he has a high school diploma. No, she says. No diploma means no enlisting.

Scott helps set her up for prenatal care. But her chance for a job and the GED are gone.

"You take two steps forward, you're going to take four back," Scott says later. "You just have to understand that. At least she has some tools now."

|

|

Type Content Here |

|

|

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

Travel

Travel

Culture

Culture

Sports

Sports

Environment

Environment

Business

Business

Bio

Bio

Photos

Photos

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog